Therefore, let’s shift our focus from the degrading portrayals of Tzombi in pop culture to the tangible and quite important contributions the Tzombi have made to human civilization. I mentioned an emergent Tzombi renaissance, and much as it vexes me that certain individuals, who are no doubt very open-minded when it comes to other issues -- the legalization of marijuana, for example -- continue to tout the virtues of offensive “zombie” films. A renaissance is generally preceded by a dark age, and though nothing could be darker for the Tzombi race than the flourishing of these offensive films in the 1960’s and 1970’s, there is nowhere to go but up (or at least co-exist with the current resurgence of the modern horror genre).

A similar dark period occurred in Greece around 1200 B.C.E. The Tzombi, fleeing persecution elsewhere, overran Greece and existed with the living in an uneasy truce. In yet another example of the way the Establishment consensus betrays the Tzombi people, one need look no further than the currently accepted translation of Thucydides On the Early History of the Hellenes, in which one passage reads: “The people were migratory, and regularly left their homes whenever they were overpowered by numbers.” If we look at the original source text, it reveals that the Greek word zontanos is here translated as “people”, when it literally means “those who live.” The word aperantos here is translated to the English word “numbers”, but it can be more literally translated as the phrase “many without end” or the words “infinite” or “undying.” The undead. While the accepted translation presents a picture of Greeks fleeing from hostile invaders, a more accurate translation reveals a displaced people searching for a home.

Eventually the Zontanos realized that, despite their sheer numbers, the Aperantos were for the most part docile and good laborers. They also discovered that they could be controlled through their fear of fire. The hearth became the center of home religion, and the defender against the Tzombi hordes. So began several hundred years Aperantos slavery.

Though slaves, the influence of the Tzombi can be felt through the artifacts of the period. The written word ceased to exist, a phenomenon in keeping with the poor eyesight of the Tzombi, and the art of the period reflected this as well. If we look at a piece of Mycenaean pottery from the era which preceded the migration of the Tzombi, we discover a wealth of realistic detail:

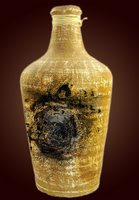

Tzombi-influenced pottery, in contrast, favors bold, abstract designs:

As previously mentioned, this “Gray Age” was followed by a glorious renaissance, which I shall attempt to document in a future entry.

1 comment:

LEGALIZE HEMP! HEMP MAKES GOOD CLOTH!

Post a Comment